Got Stones Bass If You Want It: Wyman, Woody, Keef, & Jones…

The former William Perks followed by Ronald David Wood, Keith Richards, and Darryl Jones.

By Tom Semioli

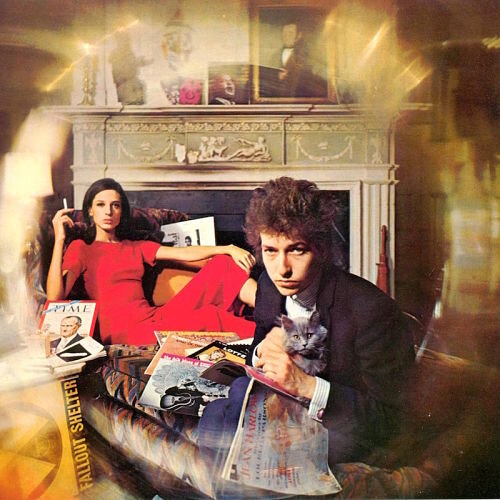

“I’m not saying they don’t keep going, but they need Bill. Without him they’re a funk band. They’ll be the real Rolling Stones when they get Bill back.” Bob Dylan as told to NME 2009

Thank you, Bob.

Born in 1960, I was too young to catch the Rolling Stones the first time around (and around) in 1964 during what we Yanks refer to as “The British Invasion.” ‘Twas not until the Edward Heath / “Tricky Dick” Nixon year of 1973 when I grabbed a fresh, newly released Goats Head Soup at Sam Goody, in Long Island, New York for $3.98 (on sale) that I became a lifelong fan.

By then, to older followers, the Stones were past their peak. But to me, they certainly were not. Massive stars in the United States, their concert treks were instant sell-outs in my homeland. Their legacy loomed large. The Stones played tough during the Joni / James / CSN & Sometimes Y/ Jackson et al. singer-songwriter zeitgeist, the disco onslaught, the blue collar Springsteen outbreak, the Johnny Rotten punks and new wave raconteurs. Jagger & Co. navigated the hard rockers and metal bands with ease – all of which were competing for young hearts and minds and ducats.

Stones Alone: If the goal is to hold the title; you have to knock out the champ. TKO. Perhaps the Stones weren’t as “relevant” as they were in earlier times: yet they could not be relegated to the canvas, albeit as they were Sucking in the 70s amid Van Halen, Fleetwood Mac, Queen, Pink Floyd…

Bruised and battered, they were still the greatest “rock and roll band” in the world. They had the songs, the chops (especially with Mick Taylor), the swagger, and the requisite panache. Heck, the Stones invented the template of a rock and roll band. Those new kids on the block – Bruce, Patti, The Ramones, Joe Strummer and The Clash – all looked up to the Rolling Stones whether it was fashionable to admit it or not.

Product such as GHS, Only Rock and Roll, and Black & Blue complimented the Bowie, Sir Elton, Roxy, Mott the Hoople, Led Zeppelin, and Bruce & E Street records which my generation spun incessantly. The Rolling Stones on automatic pilot were still tops in the general sense. By way of their new stuff, I was inspired to rummage through their past darkly and catch up on their hallowed history. Key tracks from Sticky Fingers, Exile On Main Street, Let It Bleed, and Beggars Banquet were FM radio staples throughout the decade– and shaped my generation’s vision of the band. However their 1960s canon, to my motely was ancient history, and of little interest.

Later on, as I befriended older musicians who were Stoned from the beginning, I learned of the deep cultural importance that the band had on a generation of players. Watching the Ed Sullivan Show, T.A.M.I. Show, Dean Martin Show television appearances and Gimmie Shelter film via clunky VHS tapes, I quickly came to the realization that I too would have favored the Stones (and The Yardbirds, The Animals, Cream, and Jimi) over the Fab Four solely on the raw musicianship and attitude.

No artist can approach The Beatles (and George Martin and their incredible team of engineers) as recording artists, songwriters, and conceptualists. They were too god-like. But the Stones and their aforementioned peers were within striking distance – or so it seemed. Now I understood why they were the “greatest.”

As a bass player, of course I fixated on Bill Wyman. It took years for me to fully appreciate his playing. I discovered where Bill came from: the Willie Dixon of bass. It was not easy to decipher Wyman’s work on their 70s releases. Record pressings were thin (oil crisis anyone?) with poor resonance, and decent stereo equipment was out of my economic reach. Plus, we were buying 8-track and cassettes which were aurally dreadful. Boom boxes and car radios were not much better.

When I heard my friends’ older brothers’ thick vinyl London pressings from the 1960s, mostly in mono, Bill’s artistry shone. As Keef documented in Life – they became the Rolling Stones when the former RAF (rank unknown) William Perks joined the band. On my last trip to London in 2019, I made the pilgrimage to the site where Bill became a Stone. https://youtu.be/gPrzf8hmMOY

Bill Wyman anchored The Stones for thirty years, spanning 1962 to December 1992. Fans and historians divide the Stones career into three distinct eras based on the service of their three lead guitarists: 1962-68 as the Brian Jones years, 1969-74 as the Mick Taylor years, and 1975 to the present day as the Ron Wood years.

With Brian Jones, the Rolling Stones were artists.

With Mick Taylor, the Rolling Stones were rockers.

With Ronnie Wood, the Rolling Stones are entertainers.

The Jones and Taylor versions of the band are considered the glory years. Which version reigns supreme will always be up for debate. Regardless, Bill was there.

Bill Wyman did not try to be cool. Cool tried to be Bill Wyman! Wyman’s statuesque on-stage stature and stoic veneer defined the look of the rock electric bass player – a vocation which was still rather new at the time. Due to his small body frame and hands, Bill held the bass at a nearly vertical position so he could reach the maximum number of notes with efficiency, and often employed glissandos to jump registers. Please refer to one of the greatest rock bass passages ever waxed: “19th Nervous Breakdown.”

“19th Nervous Breakdown” Live TV appearance https://youtu.be/FoNSFFhyEi8

Wyman inadvertently “invented” the fretless bass by pulling those pesky metal strips out of the neck of his whittled down Framus. As such, Bill phrased akin to an upright player with a plectrum. His lines danced around the riffs rather than simply replicating them while forging harmonic variations in the manner of a jazz player. Look no farther than “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” to hear Bill’s unmistakable harmonic / rhythmic impact on the Rolling Stones.

“(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” https://youtu.be/MSSxnv1_J2g

Albums including December’s Children, Now, 12 x 5, and Aftermath – regardless of which UK/US title you reference – along with various archival singles, b-sides, and outtakes collections, are master classes in rock bass. If you absorb Bill’s passages, you can apply them to any blues-based situation you find yourself in. And the last time I checked, blues is the foundation of rock and roll.

With drummer Charlie Watts, Wyman swung the small group Stones with a big band disposition. On up-tempo tracks, Bill avoided repetitive 8th note patterns as was the custom with “common” players, opting to vary the band’s rhythms with half notes, quarter notes, and whole notes. His note choices also had character. Bill would bring out the colors of a chord simply by emphasizing the 6th, 7th 9th notes which he would sustain. Bill’s savvy use of hammer-ons, slurs, and staccato phrasing is the stuff of elite players. You learn that from the jazz and blues cats. Not the rockers.

The faster the tempo, the more Bill put on the brakes – that’s why the Stones grooved like no other band during Wyman’s tenure. It’s an approach which never failed Bill … or me; I reference the Wyman method all the time!

Keith Cuts In: During Bill’s Stone age, his bandmate Keith Richards cut several bass tracks on their twenty-two (or so) studio albums. In her autobiography Marianne Faithful comments that Keith always had a bass in his hands and that poor Bill only played during concerts. Well, according to my ears and eyes, that’s not true.

As per the books I’ve read and researched– including Bill’s tome – Stone Alone; when fame, fortune and celebrity ensued, the band’s sessions often dragged on for hours with various hangers on, and sometimes in different countries. In many instances not all of the band members were present, hence another Stone would sub for the missing Stone. And then there were the substances…

Also take into consideration that Mr. Richards strikes me as a rather strong personality, therefore he may have simply wanted to do it all himself. And if Keith came up with a bass line, he probably cut it out of convenience, as Bill occasionally played keys or percussion on tracks with Richards on bass.

Whatever the case, Keith created a few memorable passages. Yet to my ears, they were mostly incomplete. Being the riff master that he is, Keith came up with great bass riffs. But that’s where his playing stayed – on the riff. His tone lacked warmth. His note choices are predictable. He sounds exactly like what he is – a guitar player trying to play bass until the bass player shows up. (Don’t tell him I said this….)

“Live With Me,” “Sympathy for The Devil,” “Street Fighting Man,” all have killer motifs. Though Keith fails to embellish them with any meaning.

Listen to Bill render those songs on the Stones live Get Yer Ya Ya’s Out (1970) – he does a much, much better job. Why? Because he’s Bill fooking Wyman that’s why! A bass player – first and foremost!

Keith Studio “Live With Me” https://youtu.be/R_UArnXmEZc

Bill Live “Live With Me” https://youtu.be/1gj-BYI5i-o

Keith Studio “Sympathy for The Devil” https://youtu.be/f47TZePukuQ

Bill Live “Sympathy for The Devil” https://youtu.be/qmppOF0_DHE

Keith Studio “Street Fighting Man” https://youtu.be/hU8o6usr_oU

Bill Live “Street Fighting Man” https://youtu.be/M8gPQWSXZ4I

To hear the funkiest Rolling Stones bass passage not cut by Bill, check out Mick Taylor on “Fingerprint File” (It’s Only Rock and Roll, 1974). Whereas Bill oft altered Keef’s bass parts on stage, Ronnie replicated Taylor’s passages on the live version of this track which can be found on Love You Live (1977). Wyman, sticking to his less is more credo, opted to side-up to Billy Preston and render a minimalist keyboard pad during the live performances of said composition.

Mick Taylor (studio) “Fingerprint File” https://youtu.be/V_M6lccMzek

Ronnie Wood (live) “Fingerprint File” https://youtu.be/Hcr-wMyFY2s

Note that Willie Weeks’ also cut the title track to It’s Only Rock and Roll which was recorded at Ronnie’s home studio “The Wick” in Richmond, London as he worked on his solo bow. The Glimmer Twins probably left Willie in the final mix out of handiness. Plus, Willie was a hot young player at the time, building his name with Stevie Wonder (“Misstra Know It All”) and Donny Hathaway, among others, so Weeks in the credits afforded the Stones some street cred.

Irony is, Weeks plays it like Wyman, and when Wyman plays it on Love You Live and ensuing concerts until the end of his Stones career, Bill renders more of a Willie Weeks pocket. When I meet Bill Wyman, this is the first question I will ask him!

Studio version of “It’s Only Rock and Roll” with Willie Weeks https://youtu.be/DmgCy__eUa8

Live version of “It’s Only Rock and Roll” with Bill Wyman https://youtu.be/G8X0DelcHoM

Conclusion #1: Bill should have overdubbed Keith’s bass parts. And stay the hell away from Marianne Faithful, she’s trouble!

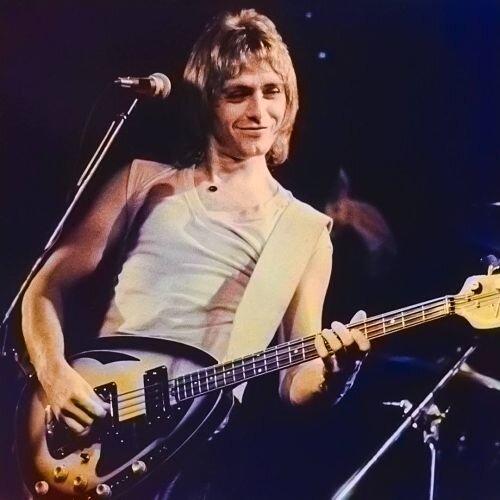

Knock On Woody: Ron Wood first came to prominence as the bass player in the Jeff Beck Group in 1968-69. Though he was primarily a guitar player, Woody’s wild personality came through on his Fender Tele bass. He never outlined the changes, he hardly sat in the pocket, his tone (mostly) lacked depth – and somehow it all worked! Woody broke all the rules – probably because he didn’t know there were any!

When Bill was unavailable and Keef wasn’t up to it, Ronnie would cut a bass track. Woody, like most guitar playing bassists opted for “box” patterns/motifs and pentatonic scales – which, to my ears, do not bring out the nuances in a chord.

The most prominent of Ronnie’s bass passages was “Emotional Rescue” – which sounds to my ears as more of a lead guitar passage rather than a supportive bass part, though he does anchor the tune in the verses. Woody also cut scattered album tracks on the Stones weaker 1980s sides which were partly recorded in New York City where Ronnie, Mick and Keith lived at the time. Those bass tracks are mostly buried in the mix.

Ronnie Wood “Emotional Rescue” https://youtu.be/U4dSIZ5QS7I

Like most guitar players who “double” on bass, Woody conjures a riff and leaves it there. Unlike the Jeff Beck records, which were given to improvisation in a blues format, Ronnie could not noodle up and down the neck with the Stones. Ronnie’s bass parts for the Stones really didn’t go anywhere harmonically or rhythmically. Neither did the songs.

I’ve Got My Own Bass Tracks to Do: If Ronnie wants to play bass again, get ahold of Jeff Beck! I’m sure they have the same hairdresser on retainer.

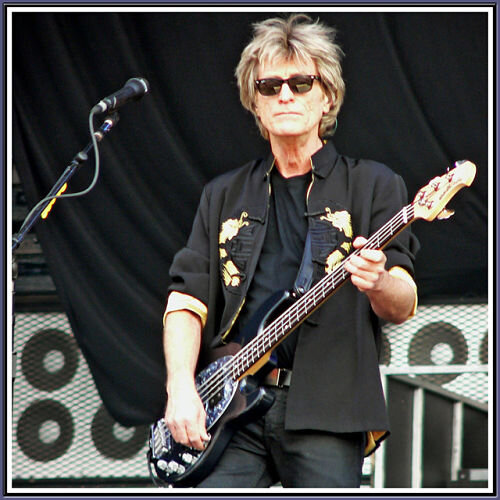

Keeping Up with The Joneses: In 1992 Bill Wyman departed the Stones to pursue other interests. After several auditions they chose Darryl Jones at the behest of jazzer Charlie Watts.

Born in Chicago (the artistic birthplace of The Rolling Stones) in 1961, Jones garnered acclaim as one of Miles Davis’ stellar bassists (along with Marcus Miller) during the jazz icon’s much heralded return in the 1980s. Jones also anchored Sting’s first solo ensemble which was massively popular, scoring several hits and videos which were on constant rotation on MTV. When one of the world’s greatest rock bass players asks you to be his bass player – I think you’re qualified for just about any rock gig!

Born on the South Side to a musical family, Jones started out as a drummer at age seven. Switching to bass when he was about nine, Darryl quickly advanced on the instrument in his teens, supporting such local jazz and blues artists as Vincent Wilburn, Matthew Rose, Perry Wilson, Otis Clay, Ken Chaney, and Phil Upchurch. Though they played the same twelve notes as the Stones, these cats were on an entirely different level that the British rock stars. Jones paid his dues with the masters.

On their 1989 -92 comeback tours (their last with Wyman) after years of inactivity, the Stones emerged as “The Rolling Stones Revue.” Darryl Jones was in his early 30s when he nailed the Stones gig in 1993, but by then they were a much different band.

In this “Revue” configuration -which more or less continues to the present day, the Stones sidemen / side-women outnumber the actual band members with three or four backup singers (including Blondie Chaplin who doubles on rhythm guitar), two keyboard players, and oft times, a horn section. Synthesizers and keyboard pads play a prominent role too, replicating string arrangements from their studio albums which adds to the illusion of even more instrumentation. Ronnie’s guitar is way down in overall mix as is Keith’s – sans for the occasional break. Sacrilege!

The Stones 21st Century sound is now slick, Las Vegas like – with virtually no room for spontaneity, though they do stretch out a bit for “Midnight Rambler” and “Can’t You Hear Me Knockin’.

You can’t always get what you want, but sometimes you get what you need. It’s great to have the Stones back and touring frequently, but now it’s only show biz entertainment rather than only rock and roll.

Given the expansive rotating roster of side players and the massive sound of the latter-day Stones, Darryl Jones mostly holds the fort with sturdy Fender Precision / Fender Jazz style instruments.

Occasionally Jones throws in a rhythmic flourish to show you that he can! But Darryl sticks to the pocket – as he should and as is necessary. He’s got a lot of people depending on him to outline the changes. On songs from the Wyman era – which comprise the majority of a Stones live set, Jones will quote the essential motifs, and return to a secure pocket.

The Stones have not recorded much with Jones – on the four studio slabs (one is a blues covers album) that he’s appeared on in nearly thirty years with the band, Jones is relegated to “roots only.” Of course, not being an official band member, Darryl does as Darryl is told! Besides, the older you get, the less notes you need to play anyway.

Whenever a band loses a member, the band changes. The dynamic changes. The power structure changes. Choosing Jones was an excellent move. I don’t think having a Bill Wyman clone would have made sense. Even though they are an established entity, it was time for the Stones to move ahead artistically.

But they didn’t. Sans Bill, the Stones swagger is more of a smooth jazz vibe. Charlie still works his swing chops, but he’s an anomaly amongst all the modern cats on the bandstand who are not Rolling Stones.

Fact is, the two “newest” members of the Stones core ensemble– one official geezer (Ronnie) and one a hired hand (Darryl) are under-used. Cherry pick tracks from any of Ronnie’s solo slabs and you’ve got another classic Stones side or two. Turn Darryl loose as did Miles and Gordon Sumner, and you’ve got a soulful cat who’ll make a lot of those sleepy album tracks percolate!

Dig Darryl’s “Miss You” bass break: https://youtu.be/YI-OzM0dy30

Darryl tears it up on “Stray Cat Blues” a (weak) bass track originally cut by Keith in the studio in ’68 https://youtu.be/PVZH7IdHP2E

Dig Darryl’s intro to “Under My Thumb” at the 51:00 mark https://youtu.be/boeEcc6hirk

Coda: Skipping Stones…

Exile on Madison Avenue?

Commencing with the recording of Exile on Main Street (which stretched from 1970- 1972), Stones bass credits begin to get sketchy. Globe-trotting jet set celebrities, tax exiles, among other titles of dubious renown, the Stones moved to Atlantic records (an American imprint) and were soon to break commercial ground by enlisting corporate sponsorship for their concert tours. The Rolling Stones were no longer a band, they were an industry.

As such, Stones records had to reach the largest audiences possible and rake in maximum revenue. Commerce took precedence over art. Which meant bringing in top session players. Rather than setting trends and experimentation, Mick & Company (and I do mean “Company”) had to keep up with vogue in the studio, on the bandstand, and in the media.

In a Guitar World interview published in January 2020, Bill discusses the well documented mayhem that surrounded the recording of the Stones tenth studio slab Exile On Main Street– a timeless twofer which stands among rocks greatest collections.

Upright bassist Bill Plummer is cited with “Rip This Joint”, “Turd on the Run”, “I Just Want to See His Face”, and “All Down the Line” recorded at Sunset Sound in Los Angeles. Mick Taylor is credited with cutting the bass tracks on “Tumblin’ Dice,” “Torn and Frayed,” “I Just Want to See His Face,” and “Shine A Light.” Keith takes ownership of “Casino Boogie,” “Happy,’ and “Soul Survivor.” Bill charges that Mick often botched the credits when he was finalizing the jacket art, and that Bill is not given credit when credit is due on Exile. Wyman also has major bones to pick about songwriting and band politics in general. He claims the riff on “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” and professes that many Stones compositions started off as studio jams only to be credited to Jagger / Richards. Such was the life of a Rolling Stone.

Who do I believe? Bill ‘fooking’ Wyman – the bass player that’s who!

Under Cover? Reggae master Robbie Shakespeare (cited in Huffington Post by this writer as a bassist deserving recognition in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the Musical Excellence category) was everywhere in the early 1980s – cutting albums with Grace Jones, Bob Dylan, Joe Cocker, Sir Mick, Garland Jeffreys, Jackson Browne, Ian Dury, and Carly Simon. Robbie’s name is on the inner sleeve of Undercover (1983), however there is no further explanation.

Undercover does not sound like a Charlie Watts / Bill Wyman album (mostly) other than the track “She’s Was Hot” which was the soundtrack one of the silliest MTV videos off all time. Dig Bill spinning the prop doghouse. And you can clearly hear Wyman’s signature motifs in this mix too.

“She Was Hot” https://youtu.be/VQh8oh0rj3s

To my ears, the rhythm section on Dirty Work (1986) does not sound or feel like Bill and Charlie on many of the tracks as well. The band were living on different continents. They were not getting along personally. Some members were given to unhealthy habits. Overdubs and/or basic tracks were cut at Right Track in New York City. The drums tracks lack Watts’ signature swing. The bass tracks are devoid of Bill’s phrasing. Considering Mick’s yen for modern technology and modern 80s sounds (gated ambience), and Watts / Wyman’s reverence for tradition, I wouldn’t be surprised if their only appearance is on the album jacket photo. Note that studio bassist John Regan is credited on the inner sleeve.

Bassists Me’Shell Ndegeocello, Doug Wimbish, John Sarli, Darryl Jones, and Pierre de Beauport, are among the bass credits of Bridges to Babylon (1997). An MOR mish-mash – there are a few good compositions here but it’s “smooth” sailing all the way. These funky cats are all kept in check – playing roots only passages – what a waste!

Wait, it gets worse… Sir Michael Phillip Jagger cut five bass tracks on A Bigger Bang (2005), a bigger dud of a Stones slab if there ever was one. Mick renders roots only, mercifully down in the mix with no harmonic or rhythmic movement. This, my readers, is the difference between a bass player and someone playing the bass until the bass player shows up. (You can tell him I said that….)

Time Waits For No One: Conclusion #2

Given the global pandemic, its residual effects, and their age, whether the Stones will ever perform or tour again is anyone’s guess. If they do return to the stage, they are not to be missed. Despite the choreography and tendency to churn out the hits with an occasional nugget, the Stones still display flashes of their former glory.

As for the bass chair, their records sans Bill, except for a few scattered tracks are best to be avoided. No disrespect to Darryl or any of the other session cats. As mentioned, I’d have favored The Glimmer Twins allowing their post-Bill bassists flexibility, and a platform to bring their unique talents to the table ala Darryl’s former boss Miles Davis (and his former boss Charlie Parker, whom Charlie Watts idolizes in more ways than just music). Miles leveraged the amazing skills of bassists Paul Chambers, Ron Carter, Darryl Jones, and Marcus Miller to his and his audience’s benefit. And to the benefit of the artform.

The Rolling Stones minus Bill played it safe. Or dare I say “Respectable.”

Among my favorite Wyman passages: “Respectable” https://youtu.be/ptDz5BwAgXQ