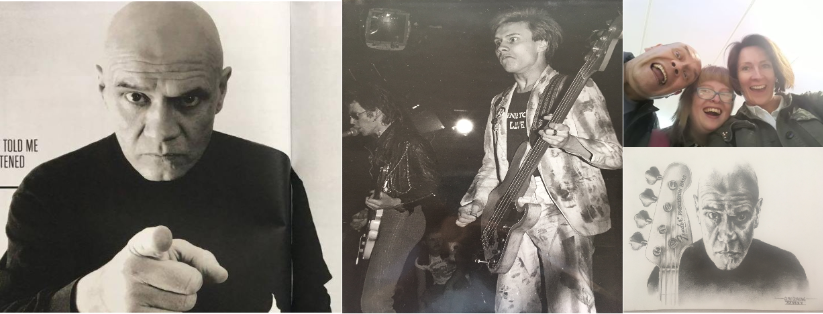

Ricardo Rodriguez by Tony Senatore

I first heard about Ricardo Rodriguez when I was hired to play bass on the Shrapnel Records release entitled Midnight Drive in 1991. At that time, Ricardo was making a name for himself as a fiery bassist in the tradition of Billy Sheehan, and we traveled in the same circles. In those days, I was known for performing 10-minute Bach inspired bass solos while clad in spandex and played on stages with smoke machines. By the mid 1990’s, I started to get some session work thanks to an introduction to the late, great engineer Jason Corsaro, and needed to radically alter my approach. Playing bass lines that were suited for the song in perfect time, with no fret rattle or buzz took precedence over trying to replicate Paganini on the electric bass. Around this time, Ricardo made similar changes to his bass style. We both made vast improvements in our bass playing, but it was not because of what we were playing, but rather what we were leaving out. Ricardo has built a career as a bassist on his own efforts. He’s not a member of the elite circle of NYC bassists that play on Broadway or do sessions at the top studios. Like me, he has built his career from the perimeter.

For all of the talk about an alleged “bass brotherhood,” I have learned that if a fraternity of elite bass players truly exists, new members are only admitted if they have something to offer in the form of a tour or a Broadway show to gain access. To truly thrive, a musician must create their own opportunities. Ricardo and I also have a similar view that there is much more to life than music. Financial security is important to us. As such, we both maintain day jobs that are unrelated to music and would not have it any other way. You can’t build a career with Instagram likes, by posing for pictures with famous bass players or “liking” their posts on Facebook. Getting hired and getting paid for your work is the only thing that matters. The rest of it is just a façade. Know Your Bass Player has always tried to convey the story of the working musician trying to navigate their way through a never-ending sea of obstacles, often in obscurity. As such, we are proud to present this feature on Ricardo Rodriguez, a true pragmatist who lives his life on his own terms.

When and where were you born?

I was born at Saint Joseph’s Hospital in Paterson New Jersey. When I was born the doctor looked at my hands and told my mom that I would either be a doctor or a musician. I was fortunate to be raised into a family full of Latin jazz musicians. Since our family functions were quite large, we would often rent a hall and my cousins and uncles would always bring the band to perform. As a kid I had no idea how good they were until I heard other bands that rarely sounded as good. They were all very well-educated schooled musicians at the top of their game. Now that I am older, I really appreciate having this influence very early on.

I am curious about your educational background or specific teachers who guided you, not limited to only music teachers.

I was always fascinated with technology and studied electronics and computer science however my mind often drifted into music land. There came a time when I was getting busier musically and so I studied theory at William Paterson and took lessons from various local professional bass players. However, my cousin Frankie was my earliest bass player influence who I looked up to and guided me. He still plays Latin jazz to this day.

Did your family support your decision to be a musician?

I put in as much time as I possibly can into my music endeavors while maintaining a day job. I’ve always been the responsible type, so my parents never gave me any arguments about my music activities. My family has always been supportive of my musical ventures. Not once has anyone given me any talk about moving in a different direction.

Who influenced you at the beginning of your career? When you listen to their work today, do your early bass influences measure up to your perceptions of them when you were young? Are there any young bass players currently on the scene that inspire you?

As early as I can remember I was always humming the bass lines to songs. Not sure why I did that to be honest. But Silly Loves Songs by Paul McCartney as well as songs like “Sir Duke” by Steve Wonder were some of my earliest influences. I had no idea what a good musician was at that age. I just knew that I was drawn to it. As time went on, I realized their genius. As far as new young bass players on the scene that I admire, Henrik Linder from Dirty Loops, Sam Wilkes from Scary Pockets, Michael League from Snarky Puppy, Joe Dart from Vulfpeck and Jacob Collier come to mind.

I am a big fan of the Carol Kaye series of bass method books. Her method, combined with The Evolving Bassist by Rufus Reid, and Bach’s Six Suites for Violoncello Solo are the backbone of everything that I do on the bass guitar. Are there any books, or YouTube video channels that have inspired you?

Great question! I have Bass Guitar for Dummies by Patrick Pfeiffer. I bought a few from this series and I loved the cds that came with them. I tend to drive a lot and loved listening to these lesson books while on the road. It really helped me absorb many things I was trying to understand at the time. I later found Patrick in NYC and took lessons from him. As for YouTube channels Scott’s Bass Lessons is my go-to, however any session bass player that records a memorable line will grab my attention. I recently found the stems to Lady Antebellum’s hit song “I Need You Now”. I removed the bass track then recorded myself playing the entire track. Craig Young is the bassist on that track. In my book that is textbook perfect bass playing.

When I started playing live in 1976, I was lucky enough to acquire a vintage Ampeg SVT. During the ’80s, I got caught up in the sterile “divide and conquer” bi-amping approach to live bass tone. These days, I prefer the character that I believe is only attainable by plugging straight into an amplifier, and I have wisely decided to revert to my roots. How has your approach to getting a great live sound evolved over the years? What was important to you in the past, and what is important today? What is your current setup?

My early influences were Steve Wonder, Parliament, and other r&b artists. I would often confuse synth bass parts for real bass parts, and I wanted synth like lows to be a part of my sound. My first serious bass cabinet had dual 18’s. In those days bigger was better. I remember an older bassist telling me I could do so much more with less and that I would let all that big stuff go one day. My first thought was no way. How boring! I lugged that beast for about five years then down sized to 15’s. I lugged the 15’s for a few years then down sized to 12’s. The 12’s, in my opinion, are the sweet spot size wise and still have those around. I held onto the 15’s thinking I would go back to them someday but never did. What I have learned is having booming bass on stage can get messy at times. Most of the time I must trim the bass down and get a more focused sound so I can hear the pitch of my notes. It’s better to let the front of house get that boomy sound and just let your stage amp be your focused monitor.

Back in 2019 a friend asked for my opinion on great combo amps. The one I had was an Ampeg Portaflex 2×8 which for its size had a great sound however they were discontinued. I told my friend I would go to a few stores and see what new amps were out there that met my approval. I hit all the stores I could find within an hour drive from my house. I was at Alto Music in Middletown. They had a bunch of Phil Jones bass amps. I tried them all including the Fender, Peavy, Ampeg, Blackstar and other brands. To my surprise the PJB BG400 kept coming out on top. I went to a few other stores that had Phil Jones amps to compare it to other manufacturers and once again the BG400 for its size kept coming out on top. The last test I did was to compare it to my Ampeg combo and the BG400 blew it out of the water. I sold my Ampeg’s and bought the BG400. Since 2019 the only amp I have gigged with is the BG400 with its extension cab. I never thought in a million years that a 5” speaker could cut it but to my surprise so far it has. So, I guess that guy who was trying to educate me in my teens was right all along. Setup, outside of the Phil Jones amps I just carry a few pedals to my live events. Nothing fancy. Just a few basic Boss pedals. Tuner, Limiter, Octave, EQ and Chorus. I love Boss pedals because I have been using them since I first started, and they never have failed me. If someone invites me to a session, I have a few boutique pedals that I will bring with me. Origin Effects Cali76 Compressor and a Noble DI. In my studio I use a Neve 1028 Preamp. It would be nice if someone would make a pedal version of this but the closest I have gotten to that is the JHS Colour Box. My travel session chain is always evolving so ask me next month what I am using.

To answer your question of what was important to me in the past and important today. That all ties into my first real recording session experience. I was only 20 years old and completely green to the process. But what I do remember was how amazing my bass not only sounded but felt under my hands. I asked the engineer a lot of questions. He explained the importance of a great preamp and compressor. All recorded bass is compressed to some degree. I like my bass to have that studio sound live, so I always add a touch of compression. Prior to knowing what a compressor was or did, the only time I experienced such a pleasant sound was with a tube amp with what is known as tube sag. A compressor mimics this sound. However not all compressors sound the same. I have a ton of them, and one will sound good with one bass and another sounds good with a different bass. So, your mileage will vary. But when you find the right combo its heaven. So, a good preamp DI, and compressor is everything these days.

Your decision to assemble a home studio to track bass parts for clients was a wise one. When asked to add bass to a project, I have yet to do the same and rely on area studios. Tell us a bit about your studio. Can you recommend a basic setup that would enable novice and veteran bass players to get started?

As much as the pandemic wreaked havoc for many it forced me into putting the studio together. I always had it in my mind of wanting to have my own recording setup, but I was always too busy and feared the learning curve. It was much easier to just show up and let someone else deal with all the technology. I just wanted to focus on playing and that’s it. I was already purchasing pieces for my studio and was already about 70% there with the gear I needed. Once we were forced to stay home and the only people that were still working musically were the ones with home studios, the rush to complete my studio went from hardly a focus to priority number one. The only problem was the whole world was in the same panic because the gear you needed was hard to come by. I ran around for a few months and spent whatever I had to get what I needed before someone one else took the opportunity away from me. What a crazy time that was.

As for setup recommendations. This topic requires a lot of discussion; however, I will try to keep it basic for now. You need a computer with lots of RAM. At least 32Gigs. Most people use Pro Tools on a MAC however I am a Windows guy and since I work in IT, I managed to put a system together that cost me 1/3rd of what an equivalent MAC would cost. So, it depends on your budget which system you want to go with. You want a good sounding interface. Apollo series of interfaces is the standard these days. Warm Audio is a decent brand that makes clones of much more expensive gear. I would check them out for a good recording DI, compressor, preamp, and microphone. As for nearfield studio monitors, Yamaha is a decent brand and would shoot for those. Lastly you can operate Pro Tools with your computers keyboard and mouse, but a control surface makes life easier. I like Icon series control surfaces. I think this covers it.

Do you make your entire living playing music? If not, why have you decided to work an unrelated day job?

My first love will always be music however personally I prefer a steady income with medical benefits. I admire the few hundred musicians that have managed to make a steady living, but I just don’t see a return to the days of the Wrecking Crew session musician life. If that were to ever happen again, I would entertain the idea of giving up my day job. Until then I just do not see paying a mortgage and car payment with on and off cash streams unfortunately.

My decision to release a solo CD in 2005, and an instructional DVD in 2007 was the catalyst for much of the session work that I am doing now. I am curious as to whether you have thought about deviating from your current path of playing on other people’s music and have considered releasing something of your own. Perhaps you have done this already, and I am unaware of it.

When I first hit the scene in the ’90’s I was only doing the New Jersey cover scene circuit. In 1999 I started working with a singer in NYC which opened a new door to session work with various singer songwriters. I was so busy that at one point I had 20 bands on rotation. Those were crazy fun times. I never gave the solo idea any thought because up until March of 2020 I was too busy working on everyone else’s projects. My mind set was always study and emulate the great session players like Pino Palladino and Nathan East.

In 2010 a Jazz band by the of Rubber Skunk hired me and for that year we had a lot of fun stretching out and I thought this might be a good band to showcase my talents but the band disbanded before we got to go into the studio. I still may one day go down that solo path but at this time I find it rewarding working with singer songwriters and bringing their ideas to life.

I have a large collection of over 40 bass guitars. If forced to get rid of all of them except for one, I would keep my 1973 Fender Precision bass. Which of the basses that you own is the instrument that you would never part with?

If forced, I would keep my Sadowsky NYC Series Chambered 5 String Bass. That bass records well and has a great neck for live playing.

It is more challenging to survive playing music today than in past eras. Reality is not negativity, and I feel an obligation to young musicians to clarify this. What would you tell them if you could offer one piece of advice to aspiring bassists?

Give music as much as you can give it but keep an eye on reality. Think about your future. One thing I try hard to do is to not get into a day job that sucks the life out of me. If you come home every day drained to the point where all you want to do is sit on your couch, then you must make some important life decisions. These types of jobs shorten your life span. Music increases it. So, find a job that will allow you to balance your creative life with your professional life. This has worked well for me so far.

Ricardo’s YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/c/RicardoRodriguezBass

Ricardo’s SoundCloud page: Stream ricardobass | Listen to Studio, Live and Demo Recordings playlist online for free on SoundCloud

Ricardo’s Instagram page: https://www.instagram.com/alotabass/