Miles Ahead: Neil Young Live at Forest Hills Stadium NYC

Just when you think you know an artist…

Previous to Neil Young & Crazy Horse’s most recent New York City concert at Forest Hills Stadium on 14 May 2024, the last time I experienced the legendary collective was circa 1978 at the Nassau Coliseum in a faraway place still known as Long Island.

Times were different, of course. Neil was a massive star, a constant presence on ubiquitous FM radio not only as a solo artist but in collaboration with Stephen Stills, Graham Nash, and David Crosby.

A role model to scores of aspiring musicians (including British new wavers Elvis Costello and Graham Parker), Neil embodied the California singer-songwriter ethos. Along with Joni Mitchell, The Eagles, and Jackson Browne, to cite a few, Mr. Young ruled from atop of his own sugar mountain.

That was then and this is now. Today, Neil’s posse is comprised of his founding rhythm section; bassist Billy Talbot, and drummer Ralph Molina – both in fine form at the ages of 80. Original guitarist Danny Whitten passed in 1972, and his replacement Frank Sampedro retired in 2014. The Crazy Horse second guitar chair now resides with Micha Nelson, son of Willie.

Now I get it….

When Neil put together Crazy Horse in 1969 – a sonic and rhythmic revolution was going on in the jazz world, and looking back, and hearing Neil in the present, methinks Mr. Young was tuned in to what was happening. And he continues to refine the template of the times.

In the 1960s standard jazz song format was giving way to free form and modal jazz – John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, the works of Alice Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, Weather Report all resounded with rock musicians spanning the Grateful Dead, Soft Machine, and Pink Floyd– and rock audiences (thank you Bill Graham, FM radio) were along for the ride. Swing tempos were replaced by funk and rock grooves. Up went the volume, out went the post-bop theme and variation solos.

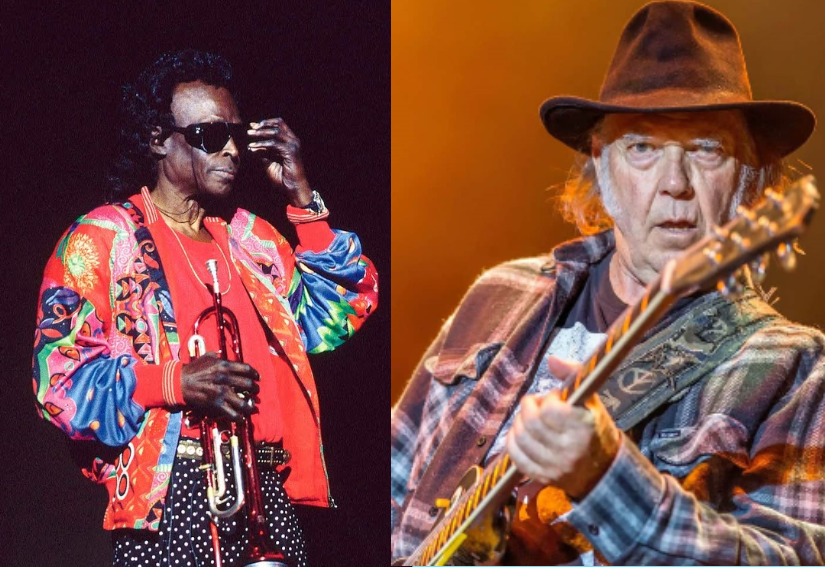

Of course, the heaviest of all the jazz rockers was Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew double album released in March 1970… which leads me to Neil and Crazy Horse.

Parallel to Miles’ ‘directions in music’ approach – Neil leads his band in the same manner. Billy Talbot, akin to Miles electric era bassist Micheal Henderson, renders sublime pedal tone grooves which anchor the ensemble and serve as motifs – and dare I say ‘hooks.’ Jazz elitists chided Henderson for his perceived simplicity. Rock musos berate Talbot for his repetitive passages – completely ignorant of their importance to the music. Like Henderson was to Miles – Talbot’s playing looms large in the essence of the Crazy Horse sound. In my jazz dub improv ensemble, I often reference Henderson’s motifs from Tribute To Jack Johnson among other Miles electric riffage – it never fails to attract (or provoke) the audience and my bandmates. From my post-punk group Tex Wagner, on record and on stage you’ll detect a few Talbot lines if you listen closely. Don’t spook the horse!

Ralph Molina, much like Davis’ range of drummers and percussionists, moves from the backbeat to polyrhythms and back to the beat again according to Young’s cues. That’s how Miles worked – always moving his players in an ongoing chess game. Nelson assumes the role of Miles’ keyboardists – he’s all texture, chordal counterpoint, and shards of sound borne of volume!

Young solos a lot like Miles as well. He comes in off the beat, usually with a few dissonant scattered notes. He stops. Like Miles advised ‘take the horn out of your mouth’ – Neil pauses before he commences his dialogue – employing effects pedals and feedback much like Davis’ used a wah-wah pedal or turned to the keyboard to add color to the brew. Though Miles had virtuosos (another dubious term) in his bands, the emphasis was on the group, not the individual. Crazy Horse blends together as one – at times you can’t distinguish the instrumentation – which strikes me as Neil’s way of doing things.

Young and Davis are/were masters of dynamics – as players and bandleaders. Rhythm, space, and collective and composition in the form of improv are/were at the forefront. Similarly, Miles and Young were reluctant to play their ‘hits’ on stage. Towards the end of their careers, they reversed said modus operandi.

Miles final performance, as captured on Miles & Quincy: Live at Montreux was recorded just two months before his death, and saw him revisit his past, rendering works he’d recorded with Gil Evans.

I’m not here to bury Neil. He is 78, in good health, and his voice hasn’t aged much. Curiously this Forrest Hills set was strictly Greatest Hits – not something you’d expect from Mr. Young, regardless of what those Alabama dudes think. Given mortality, this could very well be Crazy Horse’s victory lap.

Interesting how Miles and Neil are ‘imprisoned’ by their respective images too. Miles was the epitome of jazz cool – and still is. Thirty-plus years after his passing, the jazz police still have a warrant out for his arrest for plugging in.

Young remains a hippie icon – you can’t miss all the bootleg tie-dye merch for sale – and selling briskly – at his show. To my ears, though frozen in time to his fans, Neil left the peace and love party when it was appropriate to do so. The only thing hippie about Neil Young is his appearance – and I get the feeling that he simply dresses for comfort – just like I have embraced now at age 64.

Thirty plus years ago, 1990s alternative / grunge (awful terms, but that’s how history has recorded the era) artists recognized Neil for his experimental innovation. Ditto hip-hop artists who restored Miles experimental reputation for which he was so roundly criticized for by the jazz establishment.

In April 1970 Miles Davis opened for ‘that sorry ass cat’ (Miles’ words, not mine) Steve Miller, and Neil Young and Crazy Horse. Davis and Young were both in the throes of reinvention. Young was shedding his hippie CSN&Y skin, and Miles was running the voodoo down.

I understand from several Miles biographical sources that he was not happy on that particular bill, nor other similar circumstances with rock artists of the day. Miles learned more from Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone than the Grateful Dead – whom he also abhorred. But he was listening. And I think Neil was listening to Miles too. I hope to get the opportunity to ask him.